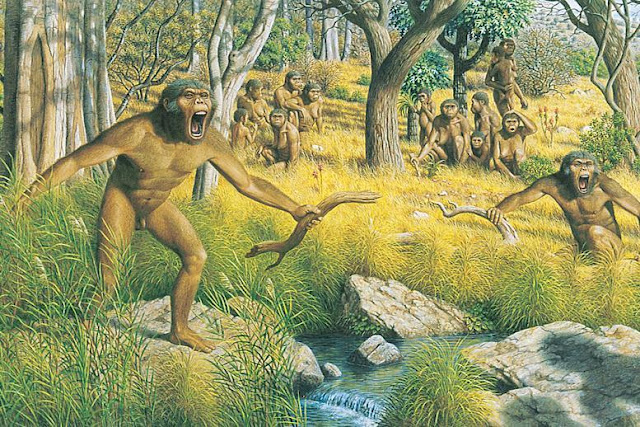

Ancient footprints in Crete challenge theory of human evolution – but what actually made them?

The oldest known human footprints, from Africa, are by Australopithecus Matheusvieeira

Researchers have discovered some 50 footprints at

Trachilos in Crete that are nearly six million years old. It looks like they

may be from a hominin – a member of the human species after separation from the

chimpanzee lineage. But, as the authors point out themselves, the findings are

highly controversial – suggesting human ancestors may have existed in Crete at

the same time as they evolved in Africa.

So what should we make of it all? If the footprints

are confirmed to be from a hominin – additional studies are needed before we

can know for sure – it is unquestionably exciting.

The oldest footprints confirmed as hominin are the

Laetoli series, which date to 3.65 million years. The Laetoli series, found in

Laetoli, Tanzania, are now known to have been made by the early human ancestor

Australopithecus. It was up to six feet tall and had a foot function pretty

much indistinguishable from our own.

Laetoli footprints, the earliest known made by humans

The candidates

So what kind of two-legged creatures have roamed

Europe or nearby countries? We have abundant fossil evidence of great apes in

Europe at the time of the Trachilos footprints, but no confirmed cases of

hominins. Apes go as far back as 13m years ago, such as Pierolapithecus from

Barcelona. Two million years later, the pongine or orangutan relative

Hispanopithecus lived in the same region. Excellent skeletons of both indicate

they were probably partially walking upright.

The ape Dryopithecus and the possible hominin

Graecopithecus from Greece were also around. The latter is about seven million

years old, but unfortunately no skeleton has been found except for skull and

teeth. Slightly older at about nine million years old are the very complete

postcranial skeletons of Oreopithecus from Italy, which was unquestionably

walking on two legs – and probably in trees as well as on ground. We don’t know

for sure, but it might also be a hominin.

In Kenya, there was Orrorin, also slightly older than

Trachilos. It lived in trees but walked on two legs, completely upright.

Orrorin was quite likely a hominin or a very close relative of the common

ancestor of chimpanzees and humans, although human-like in all ways.

Importantly though, we unfortunately lack evidence of the feet, so we cannot

compare it with the Trachilos footprints.

Slightly younger than the Trachilos prints,

Ardipithecus (from Ethiopia) is a generally accepted member of the human

lineage. Like Orrorin it could have been close to the common chimpanzee-human

ancestor, but looked more like a modern human: homo sapien. It is becoming

increasingly clear that the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees had limbs

and a trunk (a postcranial skeleton) much more like our own than like those of

living chimpanzees.

Footprints discovered in Trachilos

Gorilla prints?

So what or who made the Trachilos prints? They are

certainly convincing as real footprints, from the few pictures provided in the

paper. The age estimate of 5.7 million years also seems correct. The prints do

have a narrow heel compared to our general idea of what human footprints look

like, as the authors note. But that could easily be matched by the shape of

human footprints walking in wet mud, such as in an estuary – which may have

been the case. They have a big toe placed quite close to the others, like our

own, but so do the feet of gorillas.

Gorillas now appear to be in some respects a good

model for what the gait (and ecology) of the earliest human ancestors might

have been like, moving on two legs on the ground as well as in the trees.

The fact is that human footprints and foot function

vary enormously between steps as a consequence of the complexity of our anatomy

and ability to make choices from a large range of functional strategies to

maintain stability. Human foot pressure, which is the way force is applied over

the sole of the foot to the ground, overlaps with that of orangutans and pygmy

chimpanzees, and probably even more with that of gorillas. So in some

circumstances a human foot could look like that of a gorilla.

If all 50 of the Trachilos prints were made freely

available to other scientists as high resolution laser scans, we would have a

decent sample to assess their variability and compare them to other fossil and

recent footprints and foot pressure records. And indeed, the researchers behind

the study told The Conversation they are aiming to release all their data at

some point.

This would give us a good chance of saying who made

them. As it stands, they could as well be those of gorillas – which separated

from us over 10m years ago – as those of a member of our own human lineage such

as Oreopithecus or Orrorin.

Robin Crompton is an honorary research

fellow at the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, University of Liverpool;

Susannah Thorpe is a reader in zoology at the University of Birmingham. This

article was originally published on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Comments

Post a Comment